DAVID SEYMOUR IS DISCOVERING what Roger Douglas and Derek Quigley learned in 1994 – the first year of Acts’s existence. That the sort of supporters the party wants are pathetically few in number – far fewer than the sort of supporters it doesn’t want.

From the moment it was formed, the Association of Consumers and Taxpayers had everything a political movement needs to succeed: leaders and spokespeople who were well known; a coherent political ideology; a detailed economic programme; access to large audiences of potential supporters; and money – lots and lots of money. In Act’s first year, it has been estimated that the millionaire entrepreneur, Craig Heatley, spent one million dollars introducing the new political party to the New Zealand electorate.

On paper, Act should have succeeded, but it did not. After a year of touring the country. After a year of free media, and a million dollars’ worth of ads and pamphlets, the opinion polls showed Act hovering just below, or just over, 1 percent. Not enough. No matter how many factory owners obligingly “invited” their employees to hear Douglas’s pitch; no matter how many university campuses Quigley visited; the result was the same. At the point-of-sale, Act lacked the one thing a political movement must have to succeed: a message people want to hear.

Act’s message was liberal in the classical, eighteenth century, sense. Douglas and Quigley preached the gospel of the sovereign, self-actualising, utility-maximising individual, and located him in an economic and cultural environment where state interference is reduced to the absolute minimum. The principle Act subscribed to most enthusiastically was laissez-faire. The doctrine of laissez-faire – “allow to do” – embraced more than free markets, it looked forward to a world without bullies and/or busy-bodies. A permissive world based on the “freedom to” become the best person you can be. A libertarian world.

Or not. New Zealand’s leading Libertarian, Lindsay Perigo, walked out of the founding Act conference, denouncing its refusal to declare total war on the state, and insisting that what Douglas and Quigley were proposing was anything but libertarian. Perigo was free to split ideological hairs because he, unlike Douglas and Quigley, had no real experience of down-and-dirty retail politics. Purity and practical politics don’t mix.

Also present at Act’s founding conference, even if she had no intention of taking part, was the redoubtable left-wing activist, Sue Bradford. With considerably more political savvy than Perigo, Bradford denounced Act as an extreme right-wing party dedicated to finishing the job which Douglas had started. This description of Act was picked up by the news media and repeated ad nauseum. No matter how hard it tried, the Act Party was never able to convince the nation that Bradford’s definition was mistaken. She had branded Act for life.

Not that the “extreme right-wing” brand bothered Richard Prebble all that much. Watching from the sidelines, he was content to let Douglas discover the hard way how very few votes there were in the philosophical doctrines of the Eighteenth Century, or, for that matter, in Ayn Rand’s Objectivist fantasies of the 1940s and 50s. Prebble knew where to go looking for the votes Act needed: exactly which stones, in which dark places, it would be necessary to lift up.

Prebble understood better than just about anybody what MMP was making possible. Parties of the far-Left and the far-Right had never prospered in New Zealand for the very simple reason that the First-Past-the-Post electoral system (which the country had just discarded) made it virtually impossible for such parties to win seats. The one party which had succeeded in doing so was the Social Credit Political League, but only when popular hostility to both National and Labour was strong enough to transform Social Credit into a repository for “protest votes”. Even then, Social Credit was never able to win more than 2 seats.

Prebble was well aware that in the most propitious of political circumstances upwards of 20 percent of the electorate could be susceptible to the blandishments of a third party. Since Act could not expect many votes from the Left (not with Jim Anderton’s Alliance competing so successfully against Labour) the votes he needed belonged to those right-wing New Zealanders who believed that on matters relating to Māori, law-and-order, public morality, women, gays, unions and the environment, the National Party had aligned itself far too closely with Labour. Where is the advantage, Prebble asked his Act colleagues, in allowing Winston Peters to go on sweeping up all these votes?

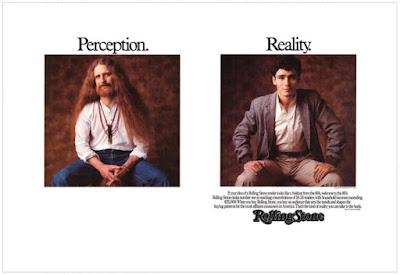

Taking his inspiration from the right-wing of the US Republican Party, Prebble set about transforming Act into a far-right populist party – albeit one represented by carefully chosen neoliberal/libertarian candidates whose personal beliefs were often at odds with the prejudices of the ideological troglodytes who voted for them. Perhaps the best historical analogy is with the “Dixiecrats” of the southern US states. From the 1940s to the 1970s, outstanding political leaders – like Senator William Fullbright – owed their seats to the votes of unapologetic white supremacists.

While Prebble led Act (1996-2004) the party polled between 6-7 percent of the Party Vote. With his departure in 2004, however, the party’s fortunes plummeted. To 1.5 percent in 2005, recovering slightly to 3.5 percent in 2008, back to 1 percent in 2011, and then to 0.7 percent under the cheerfully libertarian Jamie Whyte in 2014. In 2017, under the stewardship of Act’s incumbent leader, David Seymour, the party won just 0.5 percent of the Party Vote.

Kept in Parliament by its “Epsom Deal” with the National Party, Act seemed likely to fade into obscurity as a one-MP “appendage party”. Then, like so many aspects of New Zealand society, it was transformed by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. With National a fractious political hulk lying low in the water, many right-wing voters cast an angry protest vote for Act. From a risible 13,000 party votes in 2017, David Seymour’s party garnered a remarkable 219,000 votes in 2020 – beating Prebble’s best result (7 percent) by half a percentage point.

Seymour’s stewardship of the Act Party since 2020 has for the most part been exemplary. The party’s 9 additional MPs have presented themselves as a disciplined and competent team – offering voters a stark contrast to the bad behaviour afflicting all the other parliamentary parties. Act’s staunch defence of Free Speech, and its resolute opposition to much of the so-called “woke agenda” – especially co-governance – has pushed its numbers up and over 10 percent in the opinion polls. Not even National’s recovery under Christopher Luxon has been sufficient to seriously undermine Act’s support.

What does pose a threat to Act’s projected success on 14 October, is Seymour’s failure to be guided by Prebble’s thinking on candidate selection. Given the deeply conservative character of Act’s newfound support – much of it subscribing to the dangerous conspiracy theories growing out of the Covid-19 crisis – the need to scrutinize the party’s prospective candidates within an inch of their lives was urgent. It was absolutely vital that Act’s next ten MPs were (to continue the American analogy) William Fullbrights – not Marjorie Taylor Greenes.

The withdrawal and/or resignation of five Act candidates over recent weeks – a number of them for making claims alarmingly similar to Marjorie Taylor Greene’s – has the potential to give voters pause. Some, perhaps many, will ask themselves just how much they really know about Act and what it stands for.

Here’s a clue: it ain’t libertarianism.

This essay was originally posted on the Interest.co.nz website on Monday, 11 September 2023.