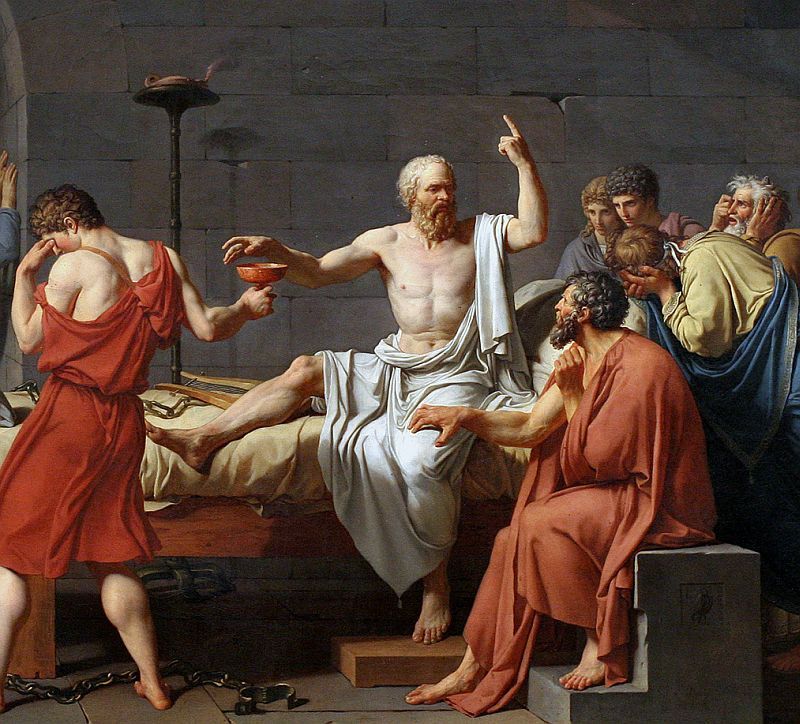

The Member For Cheshire: But is David Cunliffe grinning from ear-to-ear at the 2012 Ellerslie conference because Labour’s membership has just seized control of their party, or is it because he knows that his pathway to Labour's leadership had just been cleared?

WERE YOU TELLING THE TRUTH, DAVID? When you told your party

that the age of neoliberalism was over? That you, alone among all your

colleagues, had grasped the meaning of the global financial crisis, and only

you could lead Labour to an election victory that would restore New Zealand to

itself?

Because they believed you, David. They believed you and they

fought for you.

I remember the collective thrill that reverberated through

the party conference at Ellerslie when Len Richards told the delegates that it

was time to “take our party back!” That’s when the cameras homed in on you,

David, seated there in the midst of your New Lynn delegation (not lined up at

the microphone to oppose the democratisation of the party like so many of your

caucus “colleagues”). And you were smiling, David. You looked elated.

But, were you smiling because Labour’s membership had

finally seized control of their party, or was it because you knew that the

pathway to the leadership was now clear?

That’s what your enemies said, David. They said you looked

like a cat who’s got the cream. And, my, how they rounded on you: accusing you

of fomenting a coup against David Shearer. Do you recall the poisonous

outbursts of Chris Hipkins? Your demotion to the back benches? The vicious

harassment of your allies Charles Chauvel and Leanne Dalziel?

The ‘Anyone But Cunliffe’ faction tried to break you.

But they failed, didn’t they, David? Because, throughout it

all, the rank-and-file of the party and the affiliated trade unions remained

loyal. And, when Shearer finally threw in the towel, they knew what to do. Over

the strenuous efforts of a majority of the caucus, they elected you Leader of

the Labour Party. The moral and political lethargy of their MPs had driven the

membership close to despair – and you were their Great Red Hope.

So what happened, David?

One of the polls taken at the conclusion of the leadership

contest put Labour on 37 percent – placing it within striking distance of 41.2

percent, Labour’s best ever election result under MMP, and just a couple of

percentage points away from Labour’s winning Party Vote of 38.7 percent in

1999. You had momentum, David. New Zealanders liked your message. Labour’s

social-democratic values were threatening to come back into fashion.

And then everything went quiet. The 2013 conference, which

should have been a rapturous coronation, was a curiously strangled affair. Your

more radical supporters were “persuaded” to pull their punches on important

left-wing issues like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the age of eligibility

for NZ Superannuation. The uncompromising language of 2012’s Draft Party

Platform was watered-down to the point of blandness. Doubters were reassured

that Cunliffe was still Cunliffe. That it was a matter of priorities. That, for

the moment, “party unity” was paramount.

“Party Unity” – is that what this is all about? Party Unity.

Of the sort we saw demonstrated last week by the likes of Kelvin Davis, Phil

Goff, Chris Hipkins and Trevor Mallard? Forgive me, David, but that didn’t

strike me as evidence of a unified party. That looked to me like the ABC

Faction flexing its muscles. And you, David. How did you respond to their rank

insubordination and strategic stupidity? Did you slap them down? Did you bring

them into line? Like hell you did! You caved. Cravenly and very publicly,

David – you caved.

It’s time for you to wise up, David. The voters who thrilled

to your election as Labour’s leader won’t take much more of this. Nor will

Labour’s left-wing membership. If they had wanted a continuation of the

political lethargy and ideological flabbiness that’s characterised their

party’s parliamentary leadership since Helen Clark’s departure, then the

rank-and-file and the unions would have given their votes to somebody else.

That the Labour Left spurned your opponents was due in no

small part to their interpretation of your “The Dolphin and the Dole Queue”

speech. They simply assumed that you were readying the country for a Labour-Green

coalition, and that this combination would generate a mix of policies well to

the left of the caucus’s conservative positions. You can imagine the

alarm-bells that started ringing when Labour firmly rejected Russel Norman’s

suggestion of a joint Labour-Green campaign effort. Even more alarming was your

own use of Winston Peters’ spurious justification for giving nothing away until

after the votes have been counted.

In God’s name, man! What do you think Labour is? A minor

party! Peters’ uses his “wait until the voters have had their say” line to give

himself maximum flexibility when it comes to choosing coalition partners, and

to prevent the desertion of his supporters (who are drawn from both

the Left and the Right) by stating a clear preference for one over the other

before polling day. Are you really telling the world that Labour is now so

bereft of ideological confidence and coherence that it must resort to Winston’s

opportunistic tactics? Is that how bad things have got? That you need to trick

people into voting Labour?

Because if that is the situation, then let me tell you where

Labour is headed. It is headed in the direction of entering a Grand Coalition

with National. No, don’t shake your head in derision, in many ways the MMP

system lends itself to this solution (and in MMP’s birthplace, Germany, there

have been a least two Grand Coalition governments since 1947).

Just work your way through it logically.

If the Labour caucus is unwilling to concede ground on

policy matters to the Greens; if this is the reason so many of them would

prefer to work with the ideologically undemanding Mr Peters; and, if caucus’s

antipathy to the prospect of having to deal with Hone Harawira, Laila Harré,

Annette Sykes and John Minto is (at least) ten times greater than its hostility

towards the Greens; then what will happen if the only government (other than a

Grand Coalition) that can be formed when the votes have been counted is a Labour/Green/Internet-Mana

Party coalition?

Can you guarantee both your party and your electoral base

that the Labour caucus won’t split apart rather than accept the policy

consequences of such a radical coalition? Can you tell us that the ABCs

wouldn’t do what Labour’s Peter Tapsell did in the cliff-hanger election of

1993 – provide National the margin it needed to govern? If National was shrewd

enough to offer Labour the premiership in return for their joining a

“Government of National Unity” against “corruption and extremism”, can you

promise us you’d turn it down, David. That you’d tell National, Act, Peter

Dunne and the ABC’s to go to Hell?

Because I’m pretty sure I’m not the only person wondering

why David Cunliffe is suddenly so coy when it comes to the parties and the

policies he and his colleagues are willing to embrace. Why they cannot seem to

see the obvious electoral advantages of running a strategy of co-operation and

accommodation with the Greens and the IMP. Why it is that everybody – apart from

the Labour caucus – can see that, from a derisory 30 percent in the polls,

Labour cannot get to the Beehive on its own: that it must have allies.

You are where you are, David, because your party believed

that you would seek for those allies on the Left – not the Right. And now

they’re looking for some much needed reassurance.

So, David, tell them again: why do you want to be Labour’s

leader?

This essay was

originally posted on The Daily Blog

of Monday, 2 June 2014.