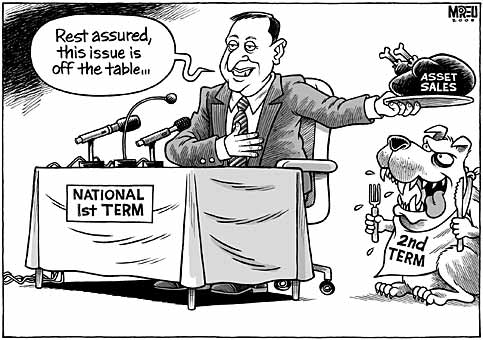

Transformer: From the benign Prime Minister of National's first term, to the dangerous Prime Minister of it second, John Key has startled those New Zealanders who'd convinced themselves they'd elected a new kind of conservative leader. Three months out from the 2011 election, and with long-forgotten numbers blasting out from the Treasury's juke-box, many New Zealanders are looking at Mr Key through new, less trusting, eyes.

NATIONAL'S MANDATE to sell state assets is indisputable. If a government goes into an election promising to sell up to 49 per cent of the state-owned energy companies' shares to private investors, and then wins more votes than its political opponents combined, well, it's hard to argue that it doesn't have a mandate.

The National Government's problem is that its mandate to "partially" privatise state assets is unusable. Prime Minister John Key may have earned the right to dilute the state's ownership of its energy companies, but it is becoming increasingly apparent that in exercising that right he would inflict so much political damage upon himself and his party that the project would become self-defeating.

The opposition to asset sales extends across the political spectrum, across all social classes, age groups and both sexes. National's election win has not changed the all-encompassing nature of this opposition. Clearly, Kiwis re-elected Mr Key's government in spite of – not because of – its policy on asset sales.

In his heart, I believe Mr Key knows this. His pollsters will certainly have registered a subtle but unmistakable shift in the electorate's mood. Like the low growl of a watchdog at the approach of an intruder, voters are signalling their displeasure at National's ideological belligerence. They hear long-forgotten tunes coming out of the Treasury's juke-box and are reminded of Roger Douglas and Ruth Richardson: people and policies they would rather forget.

New Zealanders warmed to Mr Key in his incarnation as "King Log" – the relaxed, ideologically-inert leader, who for three years floated inoffensively across the antipodean frog-pond. They are considerably less enthusiastic about Mr Key's new role as "King Stork". The last thing an electorate of frogs wants is a swift-striding leader with a murderous, spearing beak.

And Mr Key himself would do well to study the history of privatisation in New Zealand. It has never been popular, and governments which have taken advantage of their temporary possession of a parliamentary majority to strip the nation of its most valuable assets have paid a high electoral price.

When told that 90 per cent of the electorate had opposed the fourth Labour government's sale of Telecom, Richard Prebble is said to have remarked that New Zealanders should be grateful they had a government willing to resist such a large and vocal pressure-group.

That sort of arrogance is neither forgotten nor forgiven by Kiwi voters. Mr Prebble and his colleagues were thrown out of office for their disdain of democracy. And, when their National Party successors proceeded to repeat Labour's policy offences, the voters not only threw up two insurgent political parties to restrain them (the Alliance and NZ First), but they then for good measure, and as an insurance policy against future chicanery, changed New Zealand's electoral system.

Most New Zealanders, as Mr Key apparently warned the Americans in a "Wiki-leaked" diplomatic cable, are socialists at heart. Their political instincts tell them that certain industries and services should never be placed in private hands. National voters, however, should perhaps be reminded of the four great justifications for nationalisation.

One: Placing healthcare, education, energy, mass communications and transportation, and the provision of key financial services in private hands only, confers on their owners an unwarranted and potentially hazardous degree of economic, social – and so political – power.

Two: It redirects the vast revenues of these vital industries from their former private owners into the public accounts.

Three: It disperses these new revenues to the public good, especially to the protection of a natural environment despoiled by the ruthless quest for private profit.

Four: It establishes and extends the rights of employees to play a significant role in the development and management of all enterprises – public and private.

Privatisation, by reversing the direction of these progressive objectives, can only augment the wealth and power of private owners, diminish the public treasury, impede the public good, and suppress the rights of working people. It is risible to claim that your aim is to achieve these ends only "partially". Once private interests are recognised in the administration of state assets, the power to assert the public good, and defend the rights of indigenous peoples, is relinquished.

Proceed at your peril, Mr Key.

This essay was originally published in The Otago Daily Times, The Waikato Times, The Taranaki Daily News, The Timaru Herald and The Greymouth Star of Friday, 24 February 2012.