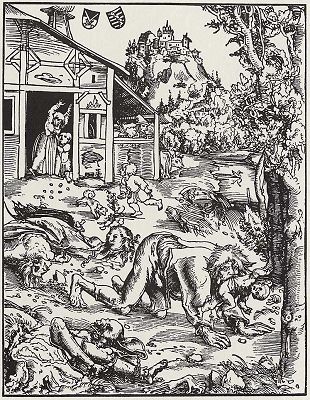

The Beast in Man: Folklore transports the conflicts of everyday social reality into a world of symbols where they can be more easily confronted and overcome. But the silver bullet that slays the werewolf, or the wooden stake that vanquishes the vampire, are magical, not substantial, remedies. Not even that modern "Philosopher's Stone" - the Internet - can free politicians from their obligation to develop real solutions to real problems in the real world.

The Beast in Man: Folklore transports the conflicts of everyday social reality into a world of symbols where they can be more easily confronted and overcome. But the silver bullet that slays the werewolf, or the wooden stake that vanquishes the vampire, are magical, not substantial, remedies. Not even that modern "Philosopher's Stone" - the Internet - can free politicians from their obligation to develop real solutions to real problems in the real world.SILVER BULLETS; wooden stakes through the heart; Philosophers’ Stones: all magical remedies for monstrous and besetting evils - and all derived from folklore.

Not that the lore of the volk should be despised, for it has much to teach us. But before we can draw any benefit from the tales of old wives, we must first learn how to read them.

The werewolf, for example, speaks to us of the beast that lurks in all men’s hearts.

Running in packs; singling out the weak and vulnerable; killing without mercy or regret; the wolf has for centuries symbolised the rapacious soldiery that laid waste to the fields and villages of a politically and militarily defenceless European peasantry. The only way to "slay" this ravening man-beast? Pay him off.

In symbolic terms: shoot him with a silver bullet.

And the vampire? The demon that does not die, but which feeds forever upon the lifeblood of its victims?

For the exploited and brutalised serfs of Eastern Europe, bled white by a parasitic class of undying aristocratic families, what more appropriate symbol of their condition could there be than the bloodsucking nosferatu?

Two things only could defeat them: the charitable ministrations of the Church; and the time-honoured remedy of assassination and revolt.

The power of the crucifix. Or, the poor man’s sword – a wooden stake – through the heart.

The Philosopher’s Stone – red sulphur – was the mythical catalyst through which, the medieval alchemists insisted, base metals could be transmuted into gold. It was also said to be the Elixir of Life, conferring upon its possessor the gift of eternal youth.

But what else is knowledge – if not the power to take the chaos and ugliness of existence and refine it into order and beauty? And don’t the insights of the wise, when put into words, live forever? Speaking to us down the ages with the same freshness and immediacy as the day upon which they were first committed to paper – or parchment?

The search for, and belief in, magical remedies is an abiding characteristic of the weak and oppressed. Folklore is their way of transporting the unconquerable realities of their lives into a universe of symbols – within which they can more easily be confronted and overcome. Soldiers become werewolves – to be brought down with silver bullets. Aristocrats become vampires – to be impaled. Chaos and ugliness – our base existence – awaits only the transmutative power of the mysterious Philosopher’s Stone.

The folklore of the 21st Century is, of course, very different from that of the Middle Ages. Ours is a more tangible age. We do not like our symbols to change shape or melt away at the touch of the first sunbeam. We believe in electronic magic.

Like the Internet.

In a world dominated by vast and powerful institutions we often feel like atoms flowing at the behest of forces we neither understand nor control. Against the corporate wolf and bureaucratic vampire we hold up the Internet as our very own version of the silver bullet; the wooden stake; the Philosopher’s Stone.

In the waste of lovelessness that is contemporary capitalism, Facebook offers an endless supply of "friends". Amidst all the white noise of corporate communications and PR spin, blogs will make us as powerful as The New York Times (or, at least, The New Zealand Herald).

Not even our politicians are immune.

Just the other day the Labour MP, Clare Curran, announced to readers of the "Red Alert" blog that her party was embarking on a bold experiment: "We want to hear all your ideas, suggestions, and the issues you think are important regards open and transparent government", says Clare. "At this stage any contribution is welcome and valid, no matter how left field."

Welcome to the virtual political party. Not for Labour the irreplaceable human chemistry of the public meeting, the branch debate, the annual conference floor-fight. No. Now you can sit in front of a keyboard and change the world – all by yourself.

No werewolf too fierce; no vampire too terrifying; no metal too base for "OpenLabourNZ"

Forgetting, of course, that politics is always made by those in the room. The real room – not the virtual town hall.

To pay-off the soldier, impale the aristocrat, learn from the wise – you have to be there and do it.

There’s no silver bullet to beat reality.

This essay was originally published in The Timaru Herald, The Taranaki Daily News, The Otago Daily Times and The Greymouth Evening Star of Friday, 7 May 2010.

5 comments:

good post dude, I like it best when your posts are relatively apolitical, you are a good writer when you keep away from New Zealand politics ,

ie

"To pay-off the soldier, impale the aristocrat, learn from the wise – you have to be there and do it"

very Napoleon Chris, perhaps you are still dangerous after all

What do you say will Jim Anderton take our Christchurch Town Hall, will this lead on to a better society down south, Jesus I hope so.

i take you so

"you have to be there" ?

Presumably telephones, TV, radio and newspapers are by the same logic irrelevant.

Leaving aside that for an increasing number of people being on the Internet is "being there"

I'm somewhat confused by this article, in that Labour are embracing the same principle that science has put to good use. Open information and expression with critical peer review are cornerstones of the scientific process, and sadly lacking in todays political systems.

The authors attachment to being in the same physical location seems to be oddly quaint in this modern connected world. Never mind the modern world of the Internet, we developed beyond the need to argue in the same room hundreds of years ago with the development of moving type.

That isn't exactly a irrelevant observation, as it was moving type; the printing press, which enabled freedom of ideas and expression that were previously the domain of the state and church.

The idea that we all have the right to express ideas and to be able to influence Government is hardly a radical idea. Voting every three years is a blunt instrument; valuable in it's ability to change Government when the fail to act in our interests, but hardly a surgical instrument when it comes to policy development.

OpenLabour is not restricting policy development to the Internet. It is opening up the policy development process to those who care enough to provide that input. It is a start to possibly introducing this concept to Government Proper; allowing for a more egalitarian mechanism for policy development.

Above all we should be applying the principles of science; policy based on the evidence and rational analysis. I have a sincere hope that this approach will lead to less ideology and development of policies which have the clear support of objective evidence.

To Laurence & Peter:

Peter, your final remarks encapsulate the fundamental misapprehension, concerning the nature of politics, under which both you and Laurence are labouring.

Both of you appear to believe politics is all about sound argument.

It is not.

Politics is about power: how it is assembled, and how it is deployed. It is about cutting deals, scratching itches, herding cats, and constantly counting the heads in both your own and your opponents' armies.

In other words, politics is an up-close-and-personal human activity. It is visceral. It is emotional. And only sometimes, if you're very, very lucky, is it rational.

You are, of course, quite correct when you say that books, telephones, radios, television, faxes and the Internet all contribute to the practice of politics. But that contribution is important only in the same way that the contribution of armaments factories and naval shipyards are important to warfare.

In the end, wars are won by human-beings killing other human-beings. It isn't rational, it isn't fair, and it most certainly isn't pretty.

This is because, in its essence (and if I may turn Clausewitz on his head) politics is merely the continuation of military activity ... by other means.

Nice one Chris. The Labour Party desperately need you!

Post a Comment