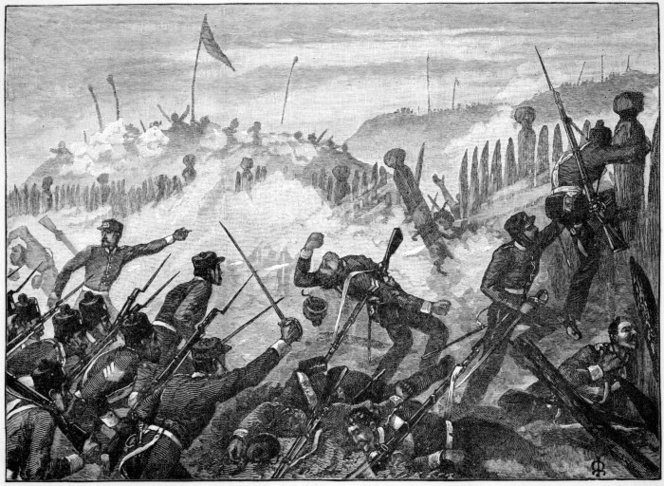

CO-GOVERNANCE presents New Zealanders with the most acute constitutional challenge since the Land Wars of the 1860s. Paradoxically, it would be a considerably less vexing problem if our ancestors truly had been the colonialist monsters of contemporary “progressive” folklore. Had the defeated Māori tribes been driven onto and confined within “reservations” – as happened to the Native Americans of Canada and the United States – instituting co-governance in the 2020s would be a breeze. Likewise, if the National Government of 1990-1999 had opted to create the New Zealand equivalent of “Bantustans” (self-governing ethnic enclaves) instead of instituting the internationally celebrated Treaty Settlement Process.

The central difficulty of the Treaty Settlement Process, as so many Māori nationalists have pointed out, is that it cannot offer more than a fraction of a cent on the dollar in terms of the current value of the Māori lands alienated under the laws of successive settler governments. To recover these from their present owners would require the outlay of hundreds-of-billions of dollars, a sum well beyond the means of even the New Zealand State – let alone individual iwi.

And yet, as the Waitangi Tribunal’s recent finding in relation to the Ngapuhi rohe makes clear, the establishment of authentic rangatiratanga is virtually impossible without the land that gives chiefly authority its political heft. With all but a tiny fraction of New Zealand presently under the control of the New Zealand State, its Pakeha citizens, and a not insubstantial number of foreign owners, any discussion of co-governance is inevitably reduced to sterile arguments over Māori representation on city councils and other public bodies.

That’s why the true underlying agenda of those who preach the gospel of co-governance can only be the re-confiscation of the tribal territories lost since the Land Wars. This may sound far-fetched, but it is not impossible. As Māori discovered in the 1860s, and subsequent decades, all that is required to deprive a people of their lands, forests and fisheries is control of the legislative process, and the military force necessary to enforce the legislators’ will.

While Pakeha New Zealanders remained united in their resolve to construct a “Better Britain” on the lands confiscated and/or acquired (all too often by immoral means) from the country’s indigenous people, the notion of re-confiscation could be dismissed as an absurdity. But, if a substantial portion of the Pakeha population, most particularly those occupying the critical nodes of state power: the judiciary, the public service, academia, the state-owned news-media, and at least one of the two major political parties; were to become ideologically disposed to facilitate the compulsory restitution of confiscated Māori resources, then the idea would begin to sound a whole lot less far-fetched.

To see how it might be accomplished one has only to study the manner in which the government of the newly-declared People’s Republic of China secured effective control of the privately-owned elements of the Chinese economy. The Communist Party of China, in sole control of the nation’s legislative machinery, and assured of a compliant judiciary and civil service, simply required private concerns to make over an ever-larger fraction of their shareholding to the Chinese state. With Boards of Directors dominated by government appointees, and no prospect of ever recovering control of their enterprises, the “owners” reluctantly sold their remaining shares to the state (receiving only a risible fraction of their true worth). The smart capitalists, reading the writing on the wall, sold-up early and fled to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and the United States. The one’s who hoped for the best, generally fared the worst.

With the news-media firmly under the Communist Party’s control, and the legal climate growing increasingly hostile to any citizen courageous enough to challenge the government’s policies, the transfer of private property into state hands was accomplished by the end of the 1950s – in less than a decade. It would have taken considerably longer if the People’s Liberation Army had not been standing behind the Communist Party’s legislators, civil servants and journalists. But, its willingness to apply military force to enforce the party’s will was never in doubt. In the words of the Chinese Communist leader, Mao Zedong: “All political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

How might a New Zealand parliament dominated by political parties favourably disposed towards co-governance set about transferring land held by private Pakeha/foreign interests to iwi authorities? One option might involve imposing all kinds of environmental and cultural obligations on landowners – obligations that could not be fulfilled without rendering the enterprise unprofitable. Crown purchase (at a fraction of the land’s true worth) would follow, allowing the state to amass a vast amount of additional real-estate. This process would undoubtedly be speeded-up by the consequent catastrophic collapse in agricultural land prices, which only constant and massive Crown purchases could stem.

With most of New Zealand land now in the possession of the Crown, returning it to tangata whenua would be the obvious next step towards meaningful co-governance. The Waitangi Tribunal, or some other, similar, body could be tasked with delimiting Aotearoa’s iwi boundaries as they existed at the time of the Treaty’s signing in February 1840. (Given that many of these boundaries would have been extended, reduced, or eliminated altogether as a consequence of the Musket Wars of the 1820s and 30s, deciding who should get what would likely entail a fair amount of ‘robust’ negotiation!)

The critical question to be settled in order for this process to succeed is whether a pro-co-governance parliament could rely upon the Police and the NZ Defence Force to enforce its legislative will. That there would be considerable resistance to the government’s plans may be taken as given, with such resistance escalating to terrorism and a full-scale armed rebellion more than likely. With the outbreak of deadly race-based violence, the loyalties of the Police and the NZDF would be tested to destruction.

Just as it required a full-scale military effort to destroy the first attempt at Māori self-government in the 1850s and 60s (an effort that divided Maoridom itself into supporters and opponents of the Crown) any second attempt to establish rangatiratanga, based on the confiscatory policies required to give it cultural and economic substance, could only be achieved militarily. That is to say, by fighting a racially-charged civil war.

Some would argue it makes more sense to accept that the historical evolution of the nation of New Zealand has actually allowed Māori to enjoy the best of both worlds. Their language and culture endure alongside their iwi and hapu connections, all very much alive beneath the overlaid institutions of the settler state.

That they are able to take full advantage of those institutions is due to the historical oddity of the colonists who created New Zealand not following the example of their white settler contemporaries and forcing the remnants of the indigenous tribes onto reservations – entities particularly suited to being “co-governed” in “partnership” with their conquerors. Instead, the Pakeha declared Māori to be full citizens, afforded them parliamentary representation, and laid the foundations of the bi-cultural society fast-emerging in Twenty-First Century Aotearoa-New Zealand.

If co-governance denotes a political system in which an indigenous people and the descendants of the settlers who joined them wrestle together with the legacies of colonisation – as free and equal citizens – then we already have it.

If co-governance denotes a political system in which an indigenous people and the descendants of the settlers who joined them wrestle together with the legacies of colonisation – as free and equal citizens – then we already have it.

This essay was originally posted on The Daily Blog of Tuesday, 17 January 2023.