THE RELUCTANCE of many left-wingers to accept that the Christchurch Shooter could not have been stopped is instructive. It betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of the motivation driving “Lone Wolf” terrorists. The perpetrators of the sort of mass killings for which Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant were convicted conceive of their actions as grotesquely “inspirational” consciousness-raising “statements”.

Precisely because these individuals operate alone; and because they accept the near certainty of being either killed or captured by the authorities; they are extremely difficult to stop. Their missions are “one-offs”. In this regard, their outrages are very different from those planned and executed by organised groups coolly intent upon securing specific political objectives through intimidation and/or terror.

In a mature democracy, like Norway or New Zealand, it is difficult to conceive of any other kind of terrorism except Lone Wolf terrorism. In the absence of deliberate violent oppression, of the sort currently on display in Myanmar, the chances of any ideological current forging a military unit of sufficient fanaticism and operational coherence to carry out a deadly terrorist attack are vanishingly small.

The nearest New Zealand has come to such a unit was the group of left-wing activists observed “training” in the Urewera Ranges more than a decade ago. It is, however, extremely unlikely that the individuals involved in these exercises could have been prevailed upon to initiate the use deadly force. It is possible that fatalities might have been inflicted inadvertently: the result of some jittery young activist transporting firearms being stopped by the Police and panicking. This is, after all, how the Baader-Meinhof/Red Army Faction’s terrorist killing began, back in the 1970s. Even so, in the context of a government presided over by Helen Clark, the Urewera “guerrillas” struck most New Zealanders as tending more towards the farcical than the tragic.

It is the sheer implausibility of organised left-wing violence that has steered New Zealand socialists toward party political alternatives. Even in the midst of the Great Strike of 1913, when armed “Red Fed” strikers exchanged shots with the “Special Constables” summoned from farming districts by the Reform Party Prime Minister, William Massey, trade union leaders understood that the vast majority of New Zealanders were on the side of law and order. This awareness of the futility of raising the red flag of revolution in a nation as red-white-and-blue conservative as New Zealand has always undermined the efforts of novelists and film-makers to persuade us that an armed left-wing guerrilla force would last longer than five minutes against the NZDF.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t work the other way around. The very same conservatism that made revolution so unlikely, has, throughout this country’s history, been more-than-willing to assist the dominant groups in New Zealand society maintain their hegemony against all-comers: Maori, Red Feds, Watersiders, Anti-Apartheid protesters. In practically every instance, however, the form of that assistance has been officially sanctioned and organised.

New Zealand had no need of a secretive racist terror-group like the Ku Klux Klan – not when an armed constabulary of land-grabbing Pakeha could be readied for action against defiant tangata whenua under the watchful eye of Settler Government ministers.

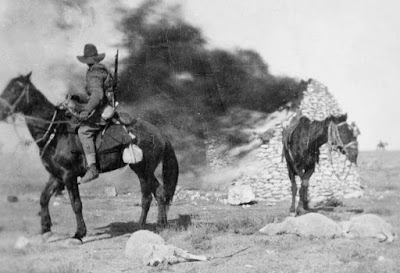

Nor did its employer class need the services of a Pinkerton Detective Agency – strike-breakers par excellence in the service of US industrial titans like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Not when the strapping sons of Waikato and Wairarapa cockies could be quietly trained and organised by army officers to serve as New Zealand capitalism’s reserve militia against the Reds – i.e. the Special Constables known forever after as “Massey’s Cossacks”. Those farmers on horseback were called out again following the Depression hunger riots of 1932.

The use of Special Constables (recruited this time from the nation’s Rugby clubs!) was also contemplated during the 151-Day Waterfront Lockout of 1951. But, thanks to the National Party Prime Minister’s, Sid Holland’s, fascistic “Emergency Regulations” (which made it illegal to feed a striker’s family) and the sterling work of the NZ Police in enforcing them, the swearing-in en masse of New Zealand’s Rugby players was not required.

Only once has the existence of a shadowy group of “unofficial” right-wing extremists, ready and willing to do whatever was necessary to preserve the capitalist status quo, come to the attention of New Zealand journalists and historians. Between 1972 and 1975, when the government of, first, Norman Kirk, and then Bill Rowling, were engaged in what was indeed a “transformation” of New Zealand society, a group of junior army officers, working secretly with elements of the SIS and the right-wing news media, began using the “C” word.

The mid-1970s was a time of threatened and actual coups against left-wing governments. In 1973, the democratically-elected socialist government of Chile was overthrown by the Chilean armed forces, and the country’s Marxist president, Salvador Allende, gunned down in his presidential palace. In 1974, Norman Kirk, obviously unwell, died alone and unattended in a second-rate Wellington hospital. His successor, Bill Rowling, was intercepted at Wellington airport by a person claiming to have documents indicating secret machinations against the Labour Government. The following year, the Australian Labor prime minister, Gough Whitlam, was deposed by his own Governor-General in a bloodless coup d’état.

That something similar did not happen here was due largely to the extraordinarily successful populist campaign waged against the Rowling Government by National’s Rob Muldoon. With a 23-seat majority, it was not considered possible for the government to be defeated. Had the political scientists been proved correct, and had Labour won a second term, who knows what those junior officers might have set in motion.

It is worth recalling that 1974 also marked the high-water mark of trade union power in New Zealand. The fear instilled in the employer class by the 10,000-strong march of workers up Queen Street to secure the release of the Moscow-aligned communist union leader, Bill Andersen – jailed for contempt of court – was palpable.

Nor should we forget that only 4 years earlier, following Allende’s 1970 victory, the US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had told his shadowy secret operations group, the “Forty Committee”, that: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

There was a hard core of far-Right activists living in mid-1970s New Zealand: some in the army; some in the SIS; some in the news media; who endorsed Kissinger’s sentiments 100 percent. Thanks to Rob Muldoon, they weren’t needed.

Those on the left of contemporary New Zealand politics, horrified by the Christchurch Mosques Attack, continue to agitate for the country’s national security apparatus to upgrade its surveillance of far-right, white supremacist, extremists. They are convinced that there is a serious threat of coordinated right-wing terrorist activity once again being unleashed against innocent New Zealanders. More preventative effort from the SIS and the GCSB is being demanded.

Unfortunately, the ability of our security agencies to thwart the attack of another Christchurch Shooter is limited. With a modicum of caution, Lone Wolf attackers can avoid detection and interception – until it is far too late.

As for an organised far-right terrorist movement unleashing horror and death in New Zealand – all of our history points to it being unlikely. Only a government with both the numbers and the will to openly challenge the capitalist system could summon forth such a movement. And when it struck, it would, almost certainly, be acting on intelligence supplied by the SIS, and wearing the uniforms of the New Zealand Defence Forces and the Police.

Our far-right terrorists have always hidden in plain sight.

This essay was originally posted on The Daily Blog of Tuesday, 30 March 2021.